A new study by researchers with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that, after years of decline, US hospitals saw significant increases in healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2020, largely as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Published today in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the analysis of National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) data from acute care hospitals in 12 states found that rates of central-line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and ventilator-associated events (VAEs) saw significant increases in 2020 compared with 2019, particularly in the second half of the year.

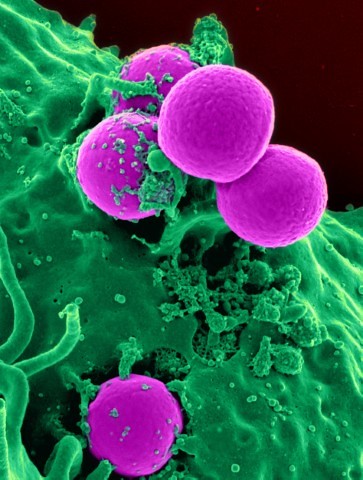

There was also a significant rise in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia.

Prior to 2020, rates of HAIs in US hospitals had been declining since 2015, a decrease that has been attributed to improved infection prevention and control measures. But the surge of COVID-19 patients in 2020—and the diversion of hospital staff and resources to focus on care of those patients—clearly put a dent in those efforts.

COVID placed a strain on resources

To get a better sense of how the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected HAI incidence, the researchers used NHSN hospital data to analyze national and state standardized infection ratios (SIRs) for 2019 and 2020. The SIR is a summary statistic that tracks HAI prevention efforts over time. It compares the number of observed infections in a facility or state to the number of infections that were predicted based on the previous year's data.

The analysis showed national SIRs for CLABSIs initially declined in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period for 2019, but then t rose by 27.9%, 46.4%, and 47% in the second, third, and fourth quarters of the year, respectively. In Arizona, the SIR for CLABSIs rose by 149% in the second quarter of 2020 compared with 2019; in Massachusetts, it doubled.

VAEs also saw significant increases, climbing by 44.8% in the fourth quarter of 2020 compared with 2019 values—an increase that could be reflective of the larger number of patients who needed ventilators due to COVID-19. CAUTIs rose by 18.8% in the fourth quarter of 2020, and MRSA bacteremia by 33.8%.

No increases were found for surgical site infections (SSIs) or Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). The authors suggest this could be because fewer surgeries were performed in 2020, while a greater emphasis on hand hygiene and personal protective equipment, combined with lower outpatient antibiotic use, may have prevented an increase in CDIs.

While the increased HAI rates could be attributed to the increase in very ill patients who needed devices such as ventilators and catheters and were hospitalized longer, the authors suggest the strain on hospital resources also played a role.

"The year 2020 marked an unprecedented time for hospitals, many of which were faced with extraordinary circumstances of increased patient caseload, staffing challenges, and other operational changes that limited the implementation and effectiveness of standard infection prevention practices," they write.

David Calfee, MD, edito r-in-chief of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology and an infection prevention and control specialist, told CIDRAP News that the findings need to be understood within the context of the pandemic and the shock and stress that it placed on the US healthcare system. He cited changes in staffing, hospitals having to create new locations of care that hadn't previously existed, and having critically ill patients cared for by staff without critical care experience as factors that could have contributed to the increase in HAIs.

r-in-chief of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology and an infection prevention and control specialist, told CIDRAP News that the findings need to be understood within the context of the pandemic and the shock and stress that it placed on the US healthcare system. He cited changes in staffing, hospitals having to create new locations of care that hadn't previously existed, and having critically ill patients cared for by staff without critical care experience as factors that could have contributed to the increase in HAIs.

"I think there were a lot of things that could have contributed to this and that you might expect could lead to the findings in this study," said Calfee, who was not involved in the research. "Certainly it wasn't business as usual in US hospitals during some of the surges in COVID-19."

In an accompanying editorial, Tara Palmore, MD, and David Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, describe how the pandemic left hospital staff with less time to devote to the type of infection prevention and control practices that have reduced HAIs in recent years.

"In a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) ward in 2020, preventing a catheter-associated urinary tract infection was probably not always the foremost consideration for healthcare staff," they write. "Nurses and doctors were trying to save the lives of surges of critically ill infectious patients while juggling shortages of respirators and, at times, shortages of gowns, gloves, and disinfectant wipes as well."

In addition, some hospital staff were asked to perform tasks they had not previously performed, such as use and care of central venous catheters. And because of limited hospital capacity and staffing shortages, Palmore and Henderson add, some hospitals had to suspend infection prevention and control programs entirely or re-direct personnel to COVID care.

"All available resources were directed at minimizing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the hospital," they write.

Call to action

The findings aren't unexpected. In late December 2020, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Society of Infectious Disease Pharmacists (SIDP), and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) wrote a letter to the Department of Health and Human Services saying that hospitals were overwhelmed and any penalties for having higher HAI rates in 2020 would be "both unfair and counterproductive."

Under rules adopted in 2009, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services adjusts its payments to hospitals based on rates of HAIs and other preventable conditions that occur during hospital stays. However, as the letter said, patient care staffing, supplies, care sites, and standard practices had all changed during the pandemic.

A December 2020 case report in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report described an outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections at a New Jersey hospital during the first wave of the pandemic. The report suggested the outbreak was likely linked to  pandemic-related resource challenges that severely limited the hospital's infection prevention and control policies.

pandemic-related resource challenges that severely limited the hospital's infection prevention and control policies.

Advocates for infection prevention and control say the increase in HAIs during the pandemic highlights the need for hospitals to have dedicated staff that can maintain infection prevention and control measures even in the face of a pandemic

In a statement, APIC President Ann Marie Pettis, BSN, RN, said the findings of the study are a "call to action."

"As a nation we must take significant efforts to bolster our infection prevention and control programs throughout the healthcare continuum," Pettis said. "We now have an opportunity to use this data and take action to invest in our public health infrastructure, expand our nation's infection prevention and control workforce, and put infection preventionists—specialists who are trained and certified to prevent infections—at the center of these efforts."

Calfee said the findings shouldn't overshadow the heroic work that US hospitals and healthcare workers have done during pandemic, nor leave people with the impression that hospitals are unsafe. But he thinks this could be an opportunity for hospitals to figure out how to be better prepared for future challenges.

"We've seen, in the years leading up to this, that we have been successful in implementing prevention strategies and reducing hospital-acquired infections," said Calfee. "Now we need to understand how we can hard-wire those practices in a way that they withstand such stresses to the system."